The academic study of music in the United States has traditionally been dominated by Western classical music and its notated scores. Applied teachers often tell undergraduate students to perform a score exactly as written, because the score reflects the composer’s intentions. This approach can make it harder for students to understand scores for what they are: historical documents that need interpretation.

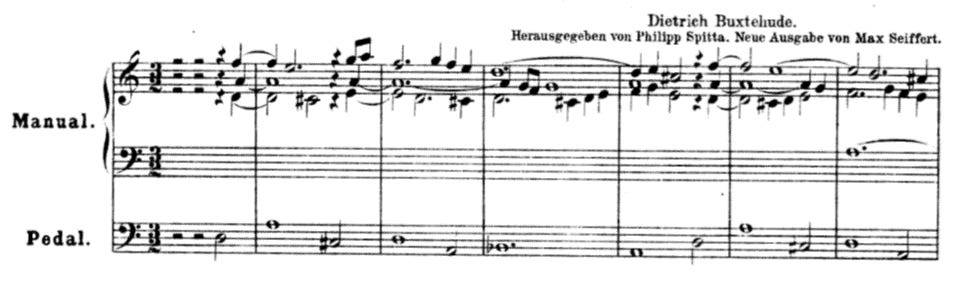

For example, suppose you find a score by the musician Dietrich Buxtehude (d. 1707), such as his Passacaglia in D minor:

There is a grand staff consisting of treble and bass clefs, labeled “manual,” and a lower staff (bass clef) labeled “pedal.” This is traditionally understood as notation for the organ, with the “pedal” part being played by the organist’s feet, and the “manual” part with the hands. There is no key signature, but the regular presence of both C-sharp and B-flat supports the idea that the music is in D minor.

These assumptions are essentially correct. Buxtehude spent over forty years (from 1668–1707) working as the organist at the Marienkirche (Church of St. Mary) in the German city of Lübeck. The piece was probably intended for the organ, although it could also have been played on a pedal harpsichord. Similarly, although modern terminology such as “D minor” hadn’t yet quite emerged in Buxtehude’s time, the music mostly follows tonal procedures and uses a D minor scale.

Consequently, reconstructing this music in performance seems like a relatively easy task. Except that it’s not. While we can come close to Buxtehude’s concept of the piece—close enough that the work concept still has use—there are a number of barriers to performing this music exactly “as the composer intended.”

1. Tuning. This score doesn’t indicate precisely what the note “A” is. Modern tuning systems tend to treat the pitch A as a multiple of 440 Hertz vibrations per second (the A above middle C is at 440 Hertz; higher As will be multiples of 440). A=440 was not established as international standard tuning until 1939, and many ensembles still deviate from it slightly, often going up to around 445. Evidence for historic tuning standards is hard to codify, but depending on the type of instrument, the time period, and the place, the note “A” could fall between 388 and 487 Hertz.

This means that in modern terms, the notated pitch A could sound anywhere from modern G to modern B. In Buxtehude’s case, we can refine this a little bit, based on the tuning of historic German organs in his era, which suggests that his A was probably somewhere between 416 and 487 (roughly G sharp to B natural), with 463 (roughly a B flat) being quite common. (As you can imagine, all these different tuning systems made it difficult to keep ensembles in tune; modern transposing instruments reflect these traditions.) The result is that it’s quite possible that Buxtehude’s “D minor” actually sounded a bit closer to our “E flat minor.”

2. Temperament. Modern keyboard instruments are tuned in an equal-tempered system, so that A-flat and G-sharp are enharmonically equivalent to each other, all semitones are the same size (about 100 cents), and all scales can exist in exact transpositions, so that keys such as D minor and E minor are intervallically equivalent. This was not always the case.

Before the eighteenth century, equal temperament was merely one option available to musicians; it was particularly associated with fretted instruments like viols and lutes. Modern equal temperament subtly adjusts (“tempers”) some notes, making them sound slightly more or less pure, producing gradual levels of dissonant “beating.” If you wanted to avoid beating and use “pure” intervals, you could explore other tuning systems, such as Pythagorean, just intonation, and mean-tone.

Such systems had serious problems. They often used unequal semitones—so that the distance between C-sharp and D was not the same as the distance between A and B-flat. Some systems distinguished between notes that are now considered enharmonic equivalents, so that D-sharp and E-flat could be different notes. Others focused on making the fifths in a given key as pure as possible. Yet often these systems meant that certain notes would naturally sound “out of tune”; Shakespeare referred to this effect in Romeo and Juliet (Act III, scene 5):

It is the lark that sings so out of tune,

Straining harsh discords and unpleasing sharps.

Similarly, keys such as C-sharp major or G-sharp minor were often unusable if the instruments were tuned to produce pure intervals in C major or G minor. (This is why so much early notated music uses keys with less than four sharps or flats.)

At the same time, these systems had a unique benefit. Because each semitone was not necessarily the same size, C major and D major scales were not exact transpositions of each other. Instead, each key had a unique sound based on its intervallic content. Because temperament and tuning were not standardized and could vary in different places, broad agreement on the exact difference between G minor and C minor was rare, although musicians left behind many contrasting descriptions of the emotional differences between each key. The modern system of equal temperament makes all the keys usable, but at the cost of each key’s unique intervallic and emotional qualities.

Buxtehude’s organ was probably tuned in mean-tone, but it might have used an experimental tuning developed by the organist Andreas Werckmeister. Similarly, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (book 1: 1724) probably used a tuning system which made all keys usable while retaining their unique qualities; today it is generally played in equal temperament, which alters the sound of the music somewhat.

3. Timbre. This is a simple point, but worth considering: the sound of the organ, including the number of stops and the sounds they produce, might have changed since Buxtehude’s time. A performance on a modern electric organ might sound different. Even using a historic instrument from Buxtehude’s time might not solve this problem unless it has been well-maintained. Pinpointing the exact timbres that Buxtehude had in mind for this piece is difficult: in later life he played an organ with fifty-four stops. One cannot simply perform this piece on Buxtehude’s own church organ, as that was destroyed in a British air raid in 1942.

4. The notation itself. So far, everything here assumes that we are indeed looking at a score written by Buxtehude, which is a faithful representation of what he meant us to see. But in fact, Buxtehude’s surviving manuscripts are generally written in organ tablature, not in lined staff notation. He might have copied his piece into staff notation himself, or someone else might have. And there might be mistakes or errors in a transcription from one form of notation to another. So how did we wind up with this music written in staff notation?

If you check the score example above again, there’s a German annotation: “Herausgegeben von Philipp Spitta. Neue Ausgabe von Max Seiffert” [edited by Phillip Spitta. New edition by Max Seiffert]. I found this score by going to the International Music Score Library/Petrucci (imslp.org), where one can download music that’s out of copyright. They helpfully provide the publication date of 1903 for this edition, which is roughly 200 years after Buxtehude’s death. Spitta (1841–1894) published an edition of Buxtehude’s music in 1876–1877, and is best-known for his multi-volume biography of J. S. Bach (finished 1880). Seiffert (1868–1948) was another music historian (Spitta’s student), who issued his own edition of Buxtehude in 1903, including updated versions of his teacher’s editions of the music. Both Spitta and Seiffert were involved in the business of establishing what Buxtehude wrote and creating a performable, readable text that contemporary musicians could play and scholars could study (organ tablature has generally fallen out of use). That means that whenever Buxtehude’s own notation was contradictory or unreadable, they would correct it and resolve any ambiguity; and if there were two contrasting versions of the piece available, they would decide which one seemed more authentic.

While both Spitta and Seiffert were respected scholars—among the foremost authorities on Buxtehude’s music in their own time—the score they created reflects their understanding of Buxtehude’s notation. The 1903 edition does necessarily not reflect the composer’s unfiltered original concept, but unless we do more research, we can’t tell how much their edition alters Buxtehude’s music.

Sometimes, editors can impose too much on a score, transforming it to meet their own agendas. Because of this, some performers prefer to use “urtext” scores, which are supposed to represent the composer’s original notation and to clearly indicate any editorial changes.

In conclusion, it’s easy to take a lot for granted when we look at a notated score. But in reality, there are a number of variables to consider. Historic scores are far less authoritative or reliable than they look.